"Lesley Dill's Poetic Visions"

"Lesley Dill's Poetic Visions"

By Adam Parker, Post and Courier

Sometimes visual art is simply meant to dazzle, shock or fascinate. Sometimes its aesthetic is superficial: it’s the surface of the work, what’s clearly visible, that communicates a fundamental idea of beauty or brutality or intricacy. Art for art’s sake.

But sometimes, art is about ideas, and what’s visible is only the outward manifestation of something larger or more significant. This is art as symbol.

Some of the best visual art, though, is a combination of the physical, intellectual and emotional. It works aesthetically while simultaneously conveying ideas of interest and resonating within us for reasons that are not always immediately clear.

For Brooklyn-based artist Lesley Dill, it is this third category that fascinates her most and drives her to create large-scale installations that mix imagery and text.

“Art is a visual philosophy as well as being visual entertainment and visual decoration, and we want to say yes to all those,” Dill said when reached by phone earlier this month.

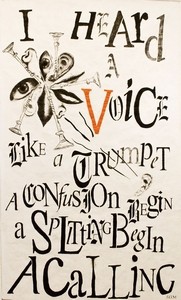

For her, words are signifiers — visual symbols — that can embody various meanings, and she uses them abundantly to create something that might be described as a cross between painting and mural.

Her work is the subject of the show “Poetic Visions,” which opened this weekend at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art and runs through March 9. The exhibition, organized by the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Wash., opened there last year and now comes to Charleston for its second (and final) showing.

Organized in conjunction with the gallery show is the Tongues Aflame Poetry Series, designed as a response to Dill’s fusion of image and language and co-sponsored by the Halsey Institute, the Poetry Society of South Carolina and the College of Charleston’s Department of English and its literary journal “Crazyhorse.” Free public readings are planned for Feb. 7, 14, 19 and 21. Celebrating intensity

Dill said she prefers a collaborative approach to art-making.

“Half the week I am ... by myself, and I am planning and thinking and reading and working,” she said. “The second half of the week, I have two assistants who work with me. And because of my lack of computer skills, which one really needs today, they really help with that. They don’t help, they take over.”

They also sprawl on the floor and help put the art together, she said. In the summer, she has up to 10 interns in the studio.

“My work is very labor intensive, very repetitive.” So she asks aspiring interns a simple question: “Can you sit in one place for eight hours and not move and make me feel that you are not unhappy?”

Recently, a prospective intern answered perfectly: “That’s my idea of heaven,” she said.

The work “Shimmer,” which Dill finished in 2006, is among her largest projects. It’s made of more than 2 million feet of thin, silvery wire strands that descend from a cryptic string of words (from a surrealistic poem by the Catalan writer Salvador Espriu) like a beard grows forth from a face: “You may laugh but I feel within me suddenly strange voices of God / and handles dog’s thirst and message of slow memories that disappear across a fragile bridge.”

The other big work that Halsey visitors can admire is “Hell Hell Hell / Heaven Heaven Heaven: Encountering Sister Gertrude Morgan and Revelation.”

This is a multifaceted installation consisting of large mural-like paintings, mannequins dressed in black and white respectively, with large letters hand-stitched to the material, and intricate cutouts mounted on the walls along the upper edge of the paintings.

The words are positioned in odd formations, creating a strong sense of motion. The trains of the dresses, also written upon, extend far back to the wall behind, sloping their way to the ceiling. This is a kind of dynamic portraiture that takes the form of a performance.

Gertrude Morgan was a New Orleans-based folk artist, street evangelist and eccentric poet who, moved by her faith in God to change her life at age 38, left her family to relocate from Georgia to the Big Easy, a den of sin and corruption, to launch her peculiar ministry. She died in 1980, but not before garnering significant attention from the art world.

Dill said she first encountered the work of Sister Gertrude at a 2004 exhibit organized by the American Museum of Folk Art. Her reaction was forceful and immediate. Here was a fellow artist who combined image and word, who thought deeply and shared a uniquely poetic vision.

“I fell in love with the freedom in her work,” Dill said.

When a New Orleans art dealer invited Dill to mount a gallery installation, she jumped at the opportunity even though she didn’t know what she would do.

“Then the idea came to me: Sister Gertrude. I’m entranced by her reverence, by her voice, by her ability to change her life and to change the way she dressed. During the first part of her life, she dressed in ecclesiastical black, then she had a vision she was the bride of Christ, so she started wearing white.”

Dill said she admired Sister Gertrude’s devotion. The black and white dresses she’s made represent aspects of the folk artist’s life and character. The enormous, flowing trains were made to reflect Sister Gertrude’s focused determination, fervor and irrationality.

“I wanted to celebrate that intensity,” Dill said.

Yet nothing about the installation is clear-cut.

“Every word opens questions about meaning,” she said. “So I think every word is a metaphysical experience.” Language of art

Halsey Institute Director Mark Sloan said the Dill show is atypical for his gallery. He likes to promote the work of “emerging artists,” those on the cusp of national or international recognition.

“This is an unusual artist for us in that she’s fully emerged,” he said. Her work has been shown in major museums and galleries. And the meaning of her art is plastic, open to various interpretations, Sloan said.

“She fuses language and image better than any artist I know,” he said.

In the smaller of the Halsey’s two gallery spaces, Dill’s Allegorical Figures made of foil are shown. These are extraordinary pieces — not quite sculpture, not quite painting — that marry text and form and celebrate dress: the way we envelop ourselves in material and the way that material expresses who we are.

“Dress of Change,” “Dress of Flame and Upside-Down Bird,” “Dress of Solace and Undoing.” These are their titles, their meaning left for the viewer to decide.

Dill, who was born in Bronxville, N.Y., and grew up in Maine by the ocean, said her parents, both teachers, inspired her, especially her mother. She was a speech and drama teacher who made her daughter comfortable with the theater.

Maine shaped her worldview, she said.

“It would start snowing at the beginning of November, and you would not see the ground until late March. My world was the shimmering grayness of the Atlantic Ocean and black trees against white snow.”

The “austere edginess” of the Maine landscape can be seen in “Shimmer” and in the Allegorical Figures.

The poetry of Emily Dickinson also has influenced Dill, and not just the poetry but the nature and character of the poet, she said. Another big influence was her two years spent in northern India. She was there in the 1990s when her husband, Ed Robbins, had a job with USAID.

“I am still amazed: Is there a foreign country you’ve ever walked into where you’ve felt like you’re home?”

She could not understand Hindi, and because just about everyone speaks English, she wasn’t required to learn it.

“So I finally encountered a language where I could let go and just listen,” Dill said. It was melodic, indecipherable, liberating. Ever since, her relationship to language has been freer, open, gauzy. She has celebrated its “up-frontness” as well as its mysteriousness and elusiveness.

At the Halsey, the spectator enters a space plush with imagery and texture and, at the same time, fragmented and strange. Loneliness and isolation are tangible. Meaning is everywhere but hard to grasp tight.

“My work does address a certain kind of introverted theatricality,” Dill said. It is a combination of modesty and amazement.