"Lesley Dill: E is for Ecstasy

At the Crossroads of Art and Literature "

"Lesley Dill: E is for Ecstasy

At the Crossroads of Art and Literature "

By Ernesto Pujol, www.abladeofgrass.org

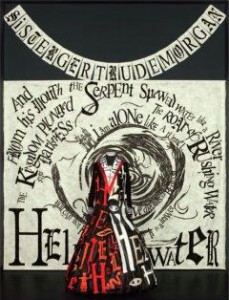

Lesley Dill’s interdisciplinary practice combines sculpture, literature and, more recently, opera. She works with text, with the material of words, the way others carve rock. We had the pleasure of attending a Buddhist retreat together at Poets’ House in Tribeca during June 2012. We bonded over our mutual love for silent walking, and devotion. Since then, we have been meeting monthly to converse about deep practice, dreaming up future performative collaborations, which can only be described as gift giving. Dill has been on the road for the past six months with several major exhibition projects. I catch her as she returns from her show, Poetic Visions: Sister Gertrude Morgan & Shimmer at the Halsey Institute in Charleston, South Carolina. She is about to receive a lifetime achievement award in printmaking from the Southern Graphics Conference International, where she will also launch a new collaborative book, I Had A Blueprint of History.

Ernesto Pujol: Can you speak about your formation?

Lesley Dill: During my childhood in Maine, I was a great reader because I was sick a lot. I had bouts of allergies, asthma, and bronchitis. I read continuously through these illnesses. In-between, I would bicycle to the library and pick up as many books as their quota allowed (which were seven), and I would read them back-to-back. In addition, I had two miraculous great aunts and a miraculous grandfather in Annisquam, Massachusetts. I say this because of the long-lasting effect they had on me. Aunts Peggy and Dorothy played an incremental Scrabble game every year, at the end of which they would gleefully add up their scores. They were also printmakers—each carving a single large linoleum block print for a year with Exacto blades. Their printed images were based on nature, on plants and animals. They would print them on fabric for the Folly Cove Designers.

Ernesto Pujol: So, those three unforgettable relatives were your first teachers.

Lesley Dill: Aunt Peggy was the first person to put a twist of colored yarn in my hand. She taught me how to weave. My grandfather taught ceramics and physics at MIT. At home, he worked in clay and Plasticine, creating busts of his children and grandchildren. He had a tree farm of over 140 acres “just to watch the trees grow,” he would say, as he walked barefoot across his land. So, he had very thick callouses on his feet, half an inch thick. He was also a silent man, barely speaking at all. “Want to go for a walk?” he would suddenly ask, and we went into the woods, walking silently, listening to the sounds of birds and leaves. He wanted me to make something of myself.

Ernesto Pujol: What about your parents?

Lesley Dill: My mother taught speech and drama at the girl’s high school I attended in Maine. She was the one who first introduced me to theater and to public speaking—the articulated publicly communicated word. I always thank her when I am on the road delivering a public talk. I also believe that she is the main influence behind my involvement with performance art today. My father had a different relationship to language. He was a paranoid schizophrenic who often had four, five or six different secret meanings to certain words. For example, if he heard the word “go,” sometimes he would do just that—he would get in the car and drive to California, returning home later during the week. The color “red” had dire meanings for him. If one of us wore a red sweater, he would perceive it as a threatening nonverbal message. It took my living in India, where red is a joyful color, to give me back an upbeat read on that color. Thus, I grew up in a “psychologically bilingual” family, widely extroverted and deeply introverted. That is how the meaning of words and the nature of language became deeply impacting for me.

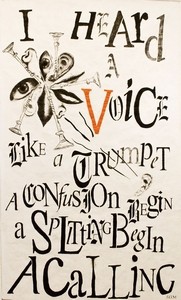

Ernesto Pujol: Not only do you find inspiration in literature, but also you use literary quotes as your content and as visual elements, as form. Can you elaborate on this?

Lesley Dill: I am a collector of words. I once had what amounts to a visual experience turned physical—incarnate—while reading. It was electric. My Mother gave me a book of Emily Dickinson’s poetry, and, as I turned the pages, phrases jumped off and flew down my throat like birds. In a place deep inside me, images for art making began to be born. I remember that experience as the beginning of what I call my Word Jump Process. Seven years later, the process reoccurred while reading other poets. It became my secret way of experiencing text. I now gather years of collected language in this fashion and knit words and phrases together into elaborate puzzles of text. I give them to the viewer as gifts. I am a recombinant collagist of sequential and non-sequential language. Every sculpture or song or drawing or print—every one has to have its own perfect skew of a linguistic attendant. I am a matchmaker of words and images.

Ernesto Pujol: How do you go about it?

Lesley Dill: I set aside a whole day, or two consecutive days for it. The word collecting process is very intense. I am nervous; I am surrounded by books and dog-eared pages of things, read and unread. I take my mind into a certain unnamable place of receptivity, and then I go, go, go—reading, scanning, swooping; turning pages steadily with an even beat; waiting for whatever word medleys will fly up and catch my ever-watchful inner eye. I really have to go into a kind of trance for this process to happen, for it to happen with truthfulness and purity. Only then, something happens.

Ernesto Pujol: Yet you also write original texts, you have a voice within the voice.

Lesley Dill: Yes, there is a throat inside the throat, like the trill of a double-throated woodland bird. I have tried to launch language from the empty bucket of my generative text mind. Nevertheless, I have to confess, the effort almost killed my mind while recently attempting that. I almost lost my intuitive recognition ability, the flow that I have always experienced. So—no more! I am just myself now, flowing again. I am a conductor of the visuality of stringed and horned words, as symphonies, or as intimate voices.

Ernesto Pujol: You have made peace with your art making process, making no demands, surrendering to your tides.

Lesley Dill: What is your process with language? I get the feeling from reading your books that you simply sit down and language flows out of you with ease, like water falling out of your pockets.

Ernesto Pujol: You are very generous in turning the tables around, asking me about my use of language. Only a true scholar of experiential language could offer me that. My sincerest response is that your insight is correct. I sit down to write about performance art, about my life and practice, and it flows out like an uninterrupted stream. In fact, I often feel as if I walk around with pockets-full of water, leaking and ready to leak. I find thinking about writing and writing about thinking very hard to contain. Perhaps I should say that, for me, writing is an obsession preceded, experienced and followed by obsessive thinking. I sit down to write fiction, my latest endeavor, the short novel, and one thought catapults another like an avalanche. My process combines what is therapeutically known as automatic writing (consciousness spontaneously mining a willing unconscious), as psychic and autistic gestures combined.

Lesley Dill: I knew it!

Ernesto Pujol: But let us turn back to you. You have also engaged in opera. How did you arrive to that medium?

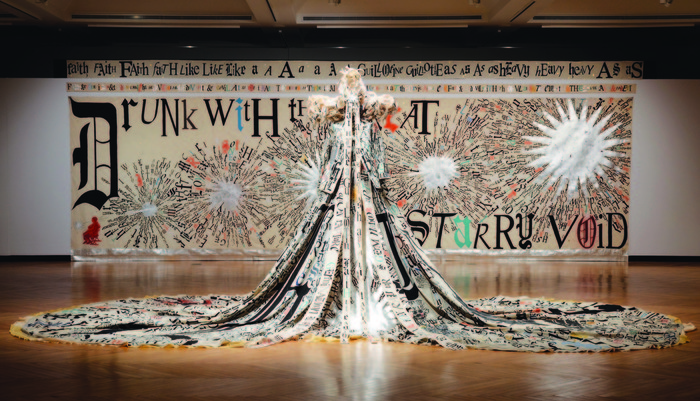

Lesley Dill: It happened at the former SOHO Guggenheim, and later, in 1995, at the Dada Ball at Webster Hall. I started choreographing performances with a woman at the center, in a symbolic dress. Four of us would slowly rip off her dress while we recited lines of poetry. Eventually, Bill T. Jones invited me to perform in a project he was curating in Paris. I felt we needed music and collaborated with Ed Robbins and Annie Murdock in creating a soundtrack. After that, every community project I did seemed to involve a choir or a chorus. In Boulder, Colorado, I found the wonderful Tom Morgan, director of the Ars Nova Singers, and we started to collaborate on an opera called Divide Light. Then—we were funded! That opened us up to more collaborators: Richard Marriott, coming in as composer, The Del Sol String Quartet, and The Choral Project, with Daniel Hughes. In the end, it was a completely amazing experience performed in 2008 at the Montalvo Art Center in San Jose, California. (Please visit www.dividelight.com)

Ernesto Pujol: Your costumes are sculpture, even as they are also scripts, long vertical and horizontal monologues with the self and others. They fold and unfold; they trail as trains. Do you conceive of them for a character in a play, an opera, or do they come to you regardless of staged narratives?

Lesley Dill: Yes! Completely. Each of the costumes I created for the opera Divide Light, as well as for shorter performance pieces, such as I Dismantle and Speaking Dress, are performing personas in their own right. In I Dismantle, the performer walks quietly in a white suit covered with the black undersides of rolled long rolls of fabric. It is as if the person is wisely but innocently carrying these identifiers on her body, as walking events. Thus, arriving at an appointed place, four attendants dressed in black slowly begin to unroll the fabric to reveal white upsides with Dickinson language on them: “A Single Screw of Flesh is All that Pins the Soul.” Like a bride, the performer is dressed in this, now totally unrolled, surrounding her, releasing language. Then, veils of white followed by orange are draped over her head.

Ernesto Pujol: It sounds so rich.

Lesley Dill: What influenced me to do it like this was traveling to Mexico and seeing the monarch butterflies with their closed grey wings during early morning. They would slowly, very slowly open their wings as the sun rose and warmed them. In choreographing the opera, I planned where each costume would appear and be activated; I calculated how many performers a single costume-activation would require. Almost every costume is a book or a scroll needing to be unrolled, opened out, spiraled around by various attendants. The final rendition of the dress is bright red, covered with the word “Ecstasy.” The performer moves across the whole stage singing “Ecstasy,” eventually rising up on a ladder, her back to the audience, slowly raising her long red gloved arms up and out with spread fingers. Then—flash! All goes black; the opera has ended.

Ernesto Pujol: You have a history of combining practices. Does this mix of disciplines come naturally, or do you make theoretical decisions about it? Because it feels very driven.

Lesley Dill: Like a wild dog in the woods looking for buried bones.

Ernesto Pujol: You have answered my question poetically, if not viscerally. Can you define devotion?

Lesley Dill: Immediate prostration of mind and body. What is it for you?

Ernesto Pujol: In this context, a disciplined dedication (rational), and an unexplainable attachment (irrational), combined in relation to something, usually an intangible. However, it could be to the material, like the environment. It could be a very secular term. And this makes me wonder: Is there a spirit of the times? Or are you above the moment (or perhaps underground), pursuing something like high wind or secret stream?

Lesley Dill: In art terms, we are in mega-eclectic times. Anyone can do anything they want, style and medium-wise. However, this is not a carefree time. We have experienced an economic downturn, which is finally hitting the art world. And New York City has suffered a natural disaster (the recent storm). We cannot ignore that.

Ernesto Pujol: You are seeking to perform more, even as you continue to make beautiful haunting objects and remarkable collages fed by ancient cultures. Tell us about your desire to walk. It is very brave.

Lesley Dill: I am engaging in walking performances—because of you! Because of my new friendship with choreographer Ernesto Pujol, who is dreaming with me about opportunities to perform, together and alone. I have practiced Buddhist walking meditation for many many years. It is wonderful to finally unite spiritual practice with my art practice, as one and the same.

Read more at >>

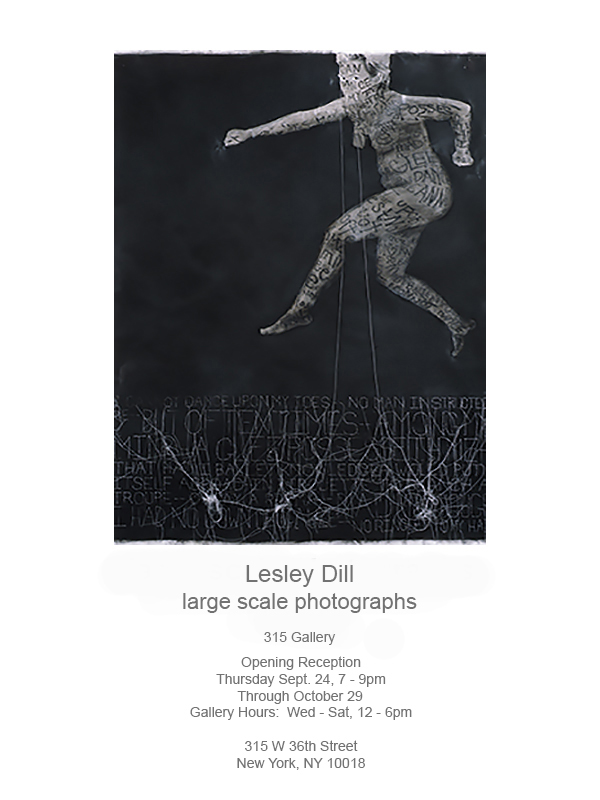

315 Gallery is pleased to present large scale photographs, an exhibition of photographs by Lesley Dill. Dill's work examines the relationship between language and the human body. Drawing on inspiration from poetry and literature, she uses text as a subject to explore the ways in which societies communicate through spoken word and physical manifestation of their bodies.

315 Gallery is pleased to present large scale photographs, an exhibition of photographs by Lesley Dill. Dill's work examines the relationship between language and the human body. Drawing on inspiration from poetry and literature, she uses text as a subject to explore the ways in which societies communicate through spoken word and physical manifestation of their bodies.